“You’re moving?” the other mother said to me.

“You’re moving?” the other mother said to me.

I looked at her in confusion.

“I am?”

Apparently, this news had come to her by way of my kindergarten-age daughter, who had announced to some of her classmates that we were moving. The impending move was news to me.

I looked at my daughter, who stared back at me impassively. Her face betrayed nothing: no guilt, no shame, no trace of wrongdoing.

“Maybe she is,” we laughed, “but the rest of us aren’t.”

A few years ago, I would have been appalled by my daughter’s bold-faced lie, which seemed to have come out of left field.

The rivers of my horror would have been deep, except that her older brother had already taken me for a swim in those waters.

A few years before at school pick up, my son’s preschool teacher and I struck up a conversation. She asked me how my husband’s job in Washington, D.C. was going. I looked at her blankly. My husband was traveling but he’d only gone a few hours away, not coast-to-coast. Had she confused me with another parent?

No, she had not.

My son, it seems, had told his class at circle time that his daddy was working in Washington, D.C. for the foreseeable future. He’d said it with such assured confidence and great specificity that multiple teachers believed it to be true.

It wasn’t the only thing that he’d said. Over the course of a week or so, he’d shared vast quantities of information with Room A: his grandparents had come to live with us, we’d had pizza for the previous night’s dinner, and he had a pet snake. Unfortunately (or fortunately in the case of the snake), none of it was true.

My heart sunk. If he could tell such off-base whoppers with panache at four, what deceptions would he be engaging in later in life?

His future flashed before me: It was a barren wasteland, full of disgrace and awash in criminality.

But his teacher, who was younger than me in years but wiser than me in the ways of children, just laughed and then proceeded to praise him. She talked about how creative he was and what an active and vivid imagination he had.

As she spoke, I took heart. I now saw him a writer, an inventor, an artist with paintbrush poised above a blank canvas. She had released him from his bleak future and freed me of my hasty misconceptions.

After that conversation, I had a talk with my son. I encouraged his imaginative wanderings and creative liberties but told him that he had to label them as such.

Several years later, my daughter and I had a similar conversation. We talked about how much fun moving sounded, and about how she had to say things like “I wish I was moving” or “Let’s pretend that I am moving” She nodded solemnly, but there were, I was sure, other imaginings dancing wildly in her head.

That conversation could have gone so many other ways, ways that would have curbed her creative expression, had my son’s teacher not shown me how to turn lies into lemonade.

When our kids are untruthful, our first instinct often isn’t to praise them – it’s to shut the lie down. We see lying as a character flaw or even a moral failing on our part. To be sure, children of all ages need to understand that lying isn’t acceptable and that dishonesty, in all forms, has repercussions, intended and unintended. But we, as parents, also need to understand that lying is a normal part of childhood. In an interview, Po Bronson, co-author of the book NurtureShock: New Thinking About Children, said that parents should expect their children to attempt lying.

When our kids are untruthful, our first instinct often isn’t to praise them – it’s to shut the lie down. We see lying as a character flaw or even a moral failing on our part. To be sure, children of all ages need to understand that lying isn’t acceptable and that dishonesty, in all forms, has repercussions, intended and unintended. But we, as parents, also need to understand that lying is a normal part of childhood. In an interview, Po Bronson, co-author of the book NurtureShock: New Thinking About Children, said that parents should expect their children to attempt lying.

Lying isn’t necessarily symptomatic of a bigger problem – it’s part of growing up and maturing. A child who lies at 5, or even 15, isn’t someone who will grow to be a cheat or an unconscientious person; they are someone exploring their world, the hard way. And lessons learned the hard way are the ones that stay with us for a lifetime.

While lying is wrong, it’s also developmentally normal.

Children are testing their power and autonomy. They’re exploring who they are and what their limits are. They’re putting their imagination and creativity to work. They’re also finding ways, desirable and undesirable, to get attention from their peers and adults.

Lying, nonetheless, is a behavior that needs to be addressed. Here are some suggestions on how to handle it.

1. Help Young Kids Learn to Differentiate Between Real and Pretend

Young kids need to be taught to say things like “this is pretend” or “this isn’t real.” For small children, the lines between fantasy and truth blur easily. It’s what allows them to have vivid imaginary friends and endless creative interactions with their stuffed animals. But even little kids can express their imaginings as “pretending.”

2. Make It Possible for Children to be Honest

Young kids, especially around the age of 4-6 years old, explore the truth. If you have a child who is having difficulty telling the truth, don’t set yourself and your child up for failure. Find a way to make it possible for them to be honest.

Young kids, especially around the age of 4-6 years old, explore the truth. If you have a child who is having difficulty telling the truth, don’t set yourself and your child up for failure. Find a way to make it possible for them to be honest.

In Your Six-Year-Old, Loving and Defiant by Louise Bates Ames and Frances L. Ig, the authors state that lying is a common problem for six-year-olds and that children in this age group are also unlikely to admit to wrongdoing. But they have a solution.

According to them, when you know your child did something wrong, like breaking a vase, don’t directly ask your child if they broke the vase. “Rather, if you must know whether he did it or not, attack the problem in a roundabout way. Ask ‘How could you reach the vase on that high shelf?’”

Another way to address lying is to describe what you saw or heard. Instead of saying, “No, that vase did not fall on its own” say, “Hmm. The way you just described the vase falling is different from what I saw. Would you like a chance to think about this?”

3. Teach Good Communication Skills

Sometimes kids lie because they don’t know any other way to share what they’re feeling or thinking.

This is often true of teenagers who may think that lying or sneaking around is the only solution, even though they know that what they’re doing is wrong.

One of the most powerful phrases we can teach children of all ages is: May I have a compromise? This gives children an effective way to be heard and it helps parents understand their children’s concerns.

In How To Talk So Kids Will Listen and Listen So Kids Will Talk, authors Faber and Mazlish say that when working toward mutually agreeable solutions, the child should suggest ideas first. Parents should “refrain from evaluating or commenting on any of those ideas. The instant you say, ‘Well that’s no good,’ the whole process ends and you’ve undone all your work. All ideas should be welcome.”

In How To Talk So Kids Will Listen and Listen So Kids Will Talk, authors Faber and Mazlish say that when working toward mutually agreeable solutions, the child should suggest ideas first. Parents should “refrain from evaluating or commenting on any of those ideas. The instant you say, ‘Well that’s no good,’ the whole process ends and you’ve undone all your work. All ideas should be welcome.”

4. Examine the Motive Behind the Lie

Every behavior has a purpose, conscious or unconscious. It’s helpful for us as parents to take a step back and listen to what our kids are really saying with their words and actions.

Are they lying because they are exploring their creative sides? Or are they trying to avoid punishment? Or because they don’t want to hurt someone’s feelings? Or because this is the behavior that has been modeled for them? Or worst of all, because they don’t think we can handle the whole truth?

Sometimes figuring out why offers more insight than what was actually said.

5. Remove the Element of Shame, For Ourselves and For Our Children

No one likes being called a liar or a cheater. Those are impactful words, both on the playground and in the home. For many of us, we overreact when our child lies because of how lying was handled when we were children: whether that be the lies we told (and the response we received) or the lies that were told to us.

No one likes being called a liar or a cheater. Those are impactful words, both on the playground and in the home. For many of us, we overreact when our child lies because of how lying was handled when we were children: whether that be the lies we told (and the response we received) or the lies that were told to us.

However, while shame is a powerful emotion, it’s an ineffective teacher. If we want to profoundly influence our kids when it comes to truth-telling, we’ll get much further by teaching about integrity and making amends than by shaming them for their behavior.

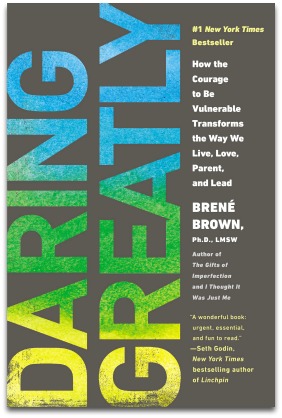

According to Brené Brown, author of Daring Greatly, shame is the “intensely painful feeling that we are unworthy of love and belonging.” But we can counterbalance shame with empathy. Even when our kids lie, the message they should hear is: We’re on the same team, let’s figure this out together.

The 2-Minute Action Plan for Fine Parents

For our quick contemplation exercise today, think of the last time your child lied to you.

- What were your first thoughts when you realized that your child was lying to you?

- How did your respond?

- Was there shame involved (either in how you felt, or how you made your child feel)?

- What might be the best way to handle the situation next time something similar happens?

The Ongoing Action Plan for Fine Parents

Over the course of the next few days, commit yourself to do these:

- Listen to what is being said and what isn’t.

- Take the time to figure out what’s motivating your child to lie. Then talk to your child about what’s behind the lies.

- Teach your child the phrase, “May I have a compromise please?” Put this phrase into practice over and over again this week.

This is very helpful. My three kids know all about the importance of telling the truth, but one in particular still struggles with it on a regular basis. Talk about alternative facts, he is a master at presenting a slightly different view of anything he has got himself into. He is 8. I work really hard to make it easy for my kids to tell the truth: there are no tellings-off if they admit wrongdoing. With him, it seems to be a matter of honour and pride that makes it impossible to tell the bare facts without embellishment. Any suggestions or advice gladly welcomed.

Thanks. Have you read NutureShock? It’s very helpful. Also, the phrases “I wish” and “Let’s pretend that” can go a long way to letting creative-types express themselves. Good luck!

Jessica, I greatly appreciate your article, mainly because the parenting style is so sensible. My children are adults now but I remember feeling like an incapable parent around a lot of parents our age because my children were given room to breath with there time and decisions. In other words, we allowed them to make decisions on as many things as possible if we felt they new the natural consequences (not ours) and it was safe physically. For example, in their teen years we allowed them to go to gatherings with friends and other kids their age. We knew there was going to be alcohol there, it’s hard to find a party for teenagers where there isn’t. We also were open with our children many times about the affects of drinking too much and addiction, etc. We told them to please stay at the party all night if they decided to drink or call us for a ride home. Now they are in there twenties and they tell us about all the friends who do goofy things from drinking too much. It’s almost like the freedom for them to discover who they wanted to be, allowed them to do so, and they were able to think about it without guilt hanging over their heads. I love the idea of not scolding them so they feel like they are a terrible person, but explaining the situation and what they need to do instead. Of course, I raised 4 children and it was my fourth child that got the best of this style of parenting!

Hi Patty. So nice to hear success from a been there, done that parent. Thanks for sharing!

Hi there. My 8 year old lies all the time, mostly to get out of trouble. She’s generally the one who embellishes her whole life (especially when talking about her friends at school) . I was wondering if this is to get attention from me as she may feel her day may have been boring??

Also how can I help her not deny all her wrong doings? She lies about taking her sisters things, about washing her teeth, about reading or doing her homework…..I just don’t any more! Please help. Thanks

It’s so tricky, isn’t it! Maybe your daughter would benefit from having a journal or writing her own book so that she has an outlet for her creativity. All of the books in the post are recommended reads!

Hi!

We are a little stumped on the compromise portion. Do you have an example of a scenario?

A very simplistic one is that you say, “Time for bed.” Your child wants to stay up 5 minutes later to finish her book, game, or whatever. She says, “Can I have a compromise please and asks to stay up 5 minutes longer. You agree on the understanding that when the 5 minutes are up, it’s bedtime (no extensions, no negotiations, etc.) I hope that helps!

“Children are testing their power and autonomy. They’re exploring who they are and what their limits are. They’re putting their imagination and creativity to work. They’re also finding ways, desirable and undesirable, to get attention from their peers and adults.”

Exactly!

Lying is a normal maybe even essential part f growing up. That’s why I hate when I hear parents telling their children that they’ll go to hell for lying.

Excellent points in your article and will add “Can we have a compromise please” to our conversations. At what age is lying a concern, though. Our 81/2 year old fits the descriptions above and thought by now she’d be outgrowing this. At what age would there be a consequence for lying?