The pandemic has likely forced most of us to experience the disappointment of plans being cancelled left, right and center. For my family, it seemed all the more special when our first holiday in two years actually went ahead. It was great to have a much-needed change of scenery and an opportunity to try new things. But there were some challenging moments, mainly in the form of hard-to-watch, hard-to-hear meltdowns!

The pandemic has likely forced most of us to experience the disappointment of plans being cancelled left, right and center. For my family, it seemed all the more special when our first holiday in two years actually went ahead. It was great to have a much-needed change of scenery and an opportunity to try new things. But there were some challenging moments, mainly in the form of hard-to-watch, hard-to-hear meltdowns!

As a mother of six-year-old twins, I had hoped that the tantrums of a two-year-old were behind us. But this holiday shone a light on how my more strong-willed daughter was finding it increasingly difficult to calm down.

My daughter’s explosions appeared to come out of nowhere and I struggled to balance the needs of both girls. My well-meaning parents provided side-line commentary on how I was ‘too soft’ on my explosive child, that it wasn’t fair on my other daughter, and I would never have behaved like this when I was her age.

In my professional life, I work with children to help them cope with life’s ups and downs. As founder of Happy Kids Coach® I am very familiar with dealing with big emotions, but when it came to my own daughter, I was finding things much tougher than normal. Her reactions triggered me in a way only your own child can!

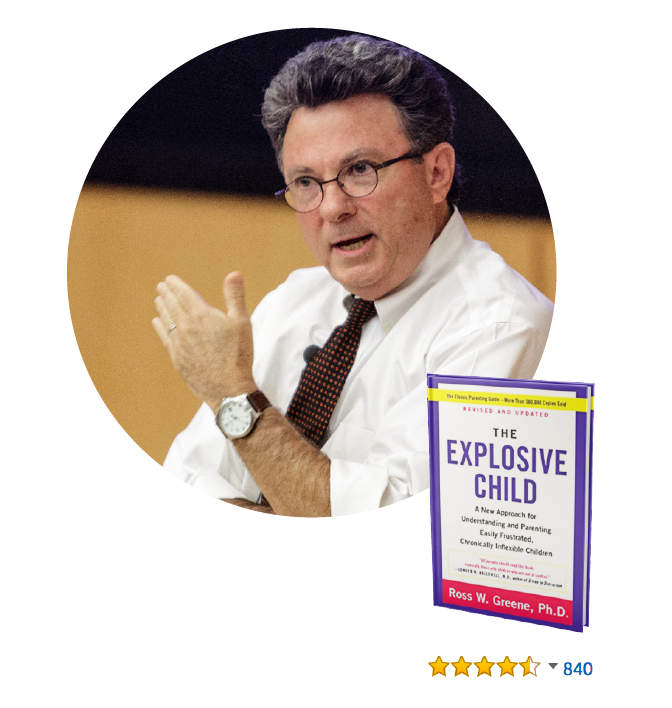

At a bit of a loss, I became a member of the AFineParent Academy and found Dr. Ross Greene’s “Collaborative and Proactive Solutions Masterclass.” His messages really resonated with me, and I was inspired to order a copy of his book, “The Explosive Child.”

Dr. Greene’s lessons gave me hope and a step-by-step plan of what to do; with amazing insight that is not only helpful to those of us with strong-willed children, but for parents of children with all temperaments. Without further ado, let’s begin the journey to a more positive and productive approach to helping our explosive children!

Step 1: What’s the Pattern?

Before we can really address behavior, we need to first understand the pattern of when meltdowns happen. Although explosive behavior may feel like it hits our daily routine like an unexpected visit from an unwelcome guest, there are always certain ingredients that create the perfect storm.

Before we can really address behavior, we need to first understand the pattern of when meltdowns happen. Although explosive behavior may feel like it hits our daily routine like an unexpected visit from an unwelcome guest, there are always certain ingredients that create the perfect storm.

To better understand the patterns behind behavior, take a few minutes to think about the following:

- Is there a specific time of day or day of the week that the behavior happens?

- What was my child doing right before the behavior happened?

- How could I tell my child was becoming upset?

- Who else was around or involved?

- What worked to calm them down?

You might notice that explosive outbursts are more likely when your child is hungry or tired. Perhaps it is when they are about to try something new or if they’re going to a new place. It might be when something unexpected has changed in their routine, or everything is rushed. For my daughter, behaviors most often happened when she was expected to share her beloved toys with a friend.

Does Charlotte’s story sound familiar? Explosive behavior can leave your head spinning! Our partnership with Dr. Ross Greene, clinical psychologist and best-selling author, gives AFineParent Academy members a front row seat to his insightful and practical solutions to explosive behaviors through the Collaborative & Proactive Solutions Masterclass.

Does Charlotte’s story sound familiar? Explosive behavior can leave your head spinning! Our partnership with Dr. Ross Greene, clinical psychologist and best-selling author, gives AFineParent Academy members a front row seat to his insightful and practical solutions to explosive behaviors through the Collaborative & Proactive Solutions Masterclass.

This packed masterclass is one of the 70+ masterclasses you get when you join the AFineParent Academy today. Click here to learn more.

Step 2: What Skills are Lagging?

Dr Greene vows that all children want to do well and will do well if they can. Our explosive, easily frustrated child is not lacking motivation but is instead lacking skills. If our child cannot do well, they need our support to build their flexibility and problem-solving skills.

Dr Greene vows that all children want to do well and will do well if they can. Our explosive, easily frustrated child is not lacking motivation but is instead lacking skills. If our child cannot do well, they need our support to build their flexibility and problem-solving skills.

If your child struggles to read, what would you do? Perhaps you’d work out what aspect they are struggling with, take it back to basics and encourage them to keep practicing. You’d likely be empathetic that all children learn to read at different paces and one day, with the appropriate support, it will click. You’d be unlikely to put a book in front of them and only give a reward if they read it perfectly or punish them if they couldn’t.

The same concept applies to our explosive kids; they do not choose to be explosive in the same way that children who have reading difficulties do not choose to struggle. Instead, explosive behavior is our child communicating that they are having a difficult time meeting an expectation because they are lacking a skill needed to do so.

What are some skills that children may lack?

- Difficulty transitioning from one activity to another

- Difficulty maintaining focus

- Difficulty managing their emotional response when they are frustrated

- Difficulty handling unpredictability

- Difficulty empathizing with others and understanding their points of view

So how can we identify what skills our child may be lacking and how can we help them develop those skills? Take a few minutes to engage with the following 3 steps:

- What specific skills are they lacking? Dr Greene’s tool can help us work this out.

- Identify examples where this is evident and write them down.

- Prioritize which area you are going to start with, and which can go on the back burner for the time being. Highlight the first ones you will work on and hold onto this list to refer back to!

Once you’ve taken some time to understand the patterns of behavior and the possible skills that our child is communicating to us that they do not have yet, it’s time to get cracking and address the problem.

Step 3: Have the Conversation

You have a list of situations where your child is likely to explode and you have chosen which one or two you want to start with. Now it’s time to address the problem with your child.

You have a list of situations where your child is likely to explode and you have chosen which one or two you want to start with. Now it’s time to address the problem with your child.

If you are like me, the thought of these conversations may be a bit daunting. I didn’t want to risk the conversation escalating into a full-blown explosion! To help the conversation go smoothly, keep these tips in mind:

- Keep behavior out of it – the focus should be on the unmet expectation rather than the meltdown which followed.

- Don’t theorize why you believe they are struggling.

- Keep it specific to one unsolved problem.

For example, instead of:

“I’ve noticed you’ve been struggling to share your toys with Ellie. I know it’s hard having play dates again after such a long time without people coming around. But screaming and lashing out at Ellie is not acceptable. She won’t want to come around here again.”

Give this a try:

“I’ve noticed you’ve been having difficulty sharing your toys with Ellie. What’s up?”

It is also helpful to focus on incorporating three stages to these conversations in order to make sure everyone feels heard and the plan put in place works for both you and your child. Keep these three stages in mind as you move through the conversation with your child.

The Empathy Stage:

If our child fell on the playground and skimmed their knee, most of us would likely react similarly: we might kneel down on the ground next to our child, give our child a hug, inspect their knee, and offer soothing words of, “It hurts when you fall, doesn’t it?”

If our child fell on the playground and skimmed their knee, most of us would likely react similarly: we might kneel down on the ground next to our child, give our child a hug, inspect their knee, and offer soothing words of, “It hurts when you fall, doesn’t it?”

Yet when explosive behaviors rear their ugly head, we too often get so caught up in the frustration or the embarrassment we feel that we may push aside how our child feels.

This can be especially detrimental to strong-willed children; however, when children feel supported and understood, they are more likely to be self-aware of their emotions and more motivated to use positive strategies to manage their emotions.

Research has shown that when parents consistently model empathetic behavior, children are more likely to develop pro-social attitudes and behavior. And contrary to some beliefs or worries, empathy does not mean that we have to lower our expectations for our child’s behavior. We can validate our child’s emotions while still holding a standard of expectations.

In the empathy stage of the conversation, it is all about better understanding your child’s point of view while keeping our own out of it! We will have a chance to state our concerns later; empathy should be the first focus of the conversation. To do this, we can focus on open-ended questions such as:

- How so?

- Can you tell me more about that?

- Using who, what, where and when questions for further information.

For example:

Me: “I’ve noticed you’ve been having difficulty sharing your toys with Ellie. What’s up?”

My daughter: “Yeah I hate sharing with her!’

Me: “How so?”

My daughter: “Because she’s mean and ruins all of my things”

Me: “Ah I see. When did she ruin one of your toys?”

My daughter: “You know, she broke the backpack of my doll!”

Me: “Oh yeah, that must have been so hard when you saw it was broken.”

My daughter: “Yeah and that’s why I don’t want her to touch anything!”

Me: “Hmm I can see how it must be hard because you don’t want that to happen again.”

Get curious and give your child the platform to speak…their answers may surprise you!

The “Your Concerns” Stage:

You’ve listened to your child’s point of view on the issue and now it’s time for you to explain your concerns.

You’ve listened to your child’s point of view on the issue and now it’s time for you to explain your concerns.

Most of the time, our concerns with an unmet expectation are related to the health, safety or learning of our child or those around them. It’s useful to have thought about this before we talk to our child. If our own reflection leads to confusion of why it is a problem, it may be because it really isn’t a problem and we are simply getting caught up in our own frustration or embarrassment of the behavior.

When sharing our concerns, we should be careful to use words appropriate for our child’s age and reasoning ability. Overloading our concern with a wordy explanation will most likely lose its value, even for an older child!

It’s also important to remember that communication is never just about the words we say. Non-verbal communication refers to:

- Using eye contact

- Having open body language

- Ensuring our facial expressions remain relaxed

- Keeping an ear out for our tone and volume

Non-verbal communication is arguably just as important as the words we say. If we share our concerns with an agitated tone of voice or annoyed facial expression and body language, we may see our child shut down quickly. To avoid this, we can be careful to keep positive and calm in our nonverbal communication, while also sharing our concerns with simple words. For example:

- For a child who struggles with sharing, we might say, “The thing is, sharing is an important skill and if you don’t practice, it will always feel hard. Also, if you push your friend when she plays with your toys incorrectly, I am worried about her getting hurt.”

- For a child who won’t do their homework, we might say, “The thing is, I worry that if you don’t do your homework, you will find it hard to know what’s going on in class as you haven’t practiced what you’ve learned.”

- For a child who refuses to clean their teeth, we might say, “The thing is, if you don’t clean your teeth then you could get cavities. Not only could this be painful, but it could also cost us a lot of money at the dentist.”

Sharing our concerns should never be a guilt trip; instead, we can focus on stating the facts about why something matters to us. Having both sides on the table makes it easier to know what needs to be achieved in the next and final step: finding a solution that meets both of your needs.

The Problem-Solving Stage:

The final stage is the invitation to form a problem-solving team. The words “I wonder if we can think of a way….” will come in handy here!

For my daughter who often struggled with sharing skills, problem solving was initiated with the statement “I wonder if we can think of a way for you to share toys with your friend without worrying that she will break something. Have you got any ideas?”

You might be met with a wall of silence, or your child might have a suggestion. Either way, it’s good to give them an opportunity to come up with an idea first.

If their suggestion solves their concerns but not yours, a simple statement such as, “I think that sounds like a good idea for you, but it doesn’t work so well for me” can allow the conversation to continue.

For my daughter, problem solving about how to help her share landed us on a plan for her to put away the toys most precious to her before her friend came to play. She would then be able to practice sharing with toys that she was less emotionally attached to. If she was worried about things getting damaged, she knew she could call on me for help.

Problem solving is a team effort and the solution needs to be something realistic and mutually satisfactory. Not only can we act as a facilitator and observer in the problem-solving process, but we can also act as a supporter–providing encouragement and acknowledging the hard work our children put in to finding a solution.

With my daughter, we found that writing down potential solutions and crossing off ones that didn’t work for one of us was a good way for her to know we were serious about finding a solution. The chosen solution was put on a post-it on the fridge to remind us of what we had agreed upon. We practiced our chosen plan a few times and it worked very well, but we always had our list to go back to in case we had to try a new idea.

I now have a dedicated problem-solving notebook to remind me of the steps and the solutions we came up with using empathy, sharing our concerns, and an invitation to problem solve. It is a comforting record to see the progress that has been made and it allows for reflection on how past hurdles are no longer problems as she has made growth on those lagging skills.

Your child will do well if they can. If they can’t, this is often due to lagging skills such as low frustration tolerance, not manipulation. When talking to your child, try to remain open and leave your own assumptions and predetermined ideas out of it.

When you first start this approach, it can feel quite daunting, but there’s no pressure to complete all three steps in one sitting. Once you’ve both aired your concerns, you might need some time to think about some possible solutions. The more you use this approach and the more problems you are able to tick off, the easier and more rewarding it gets!

The 2-Minute Action Plan for Fine Parents

If you have not already done so while reading, take a few minutes to journal or think about the following:

- When do my child’s meltdowns happen?

- What skills could my child possibly lack (which are contributing to an inability to meet expectations)?

- Which situations would I like to address first?

- When is a good time to sit down and have a conversation with my child?

The Ongoing Action Plan for Fine Parents

This collaborative problem-solving approach gets easier the more you do it, so even if the first few conversations don’t run smoothly, it’s important to use our own skills of persistence to keep going! Over the next few days and weeks, focus on being consistent in a change of mindset that will allow you to:

- Better understand the when and why for each meltdown.

- List out all of the situations where meltdowns occur and pick one to start with while putting the others on the backburner.

- Prepare to have the conversation by:

- Listening to your child’s point of view, giving them a platform to share and leaving your assumptions behind.

- Sharing your opinion on why the behavior is an issue and how it’s impacting the child or people around them.

- Brainstorming ideas as a team and start with one which is realistic and mutually satisfactory.

Great article – thank you!