I was sexually molested by a relative from the age of eight to fourteen.

I was sexually molested by a relative from the age of eight to fourteen.

Later in my teen years, several other men, strangers, approached me and tried to have sexual interactions.

I felt like I had the proverbial sign above my head. “Easy target. Pick her.”

Back then, I had no idea why. Now, I understand.

My low self-esteem. My assumptions that sexual things were secret, dirty, and unspoken. My belief that my feelings weren’t valid.

All those, indeed, put an invisible sign over me that predators, who know what they’re looking for and know how to spot it, could easily see.

I am a #MeToo girl, but I’ve worked to make sure my three girls don’t have to say that. No one wants to think about their little girl or boy being sexually traumatized. We know, though, that given the plethora of #MeToos and the cultural landscape, we need to prepare our children for the possibility.

Yet many of the popular ideas out there for teaching our girls are so negative. Don’t wear this. Don’t go there. Don’t act this way. This is actually the opposite of what girls need to have a healthy outlook on their bodies and their rights.

Boys, on the other hand, may learn that they’re supposed to be tough, rub some dirt in it, and never cry. They’re expected to aim for sports fame and leadership. A boy who has no interest in those activities can feel left out of social interaction, vulnerable to someone who tries to isolate him even more. Boys who don’t fit the “tough” mold aren’t as likely to tell someone they’re being abused, fearing that “telling” is proving their own weakness.

Ted Bunch from A Call to Men insists that parents should strive not to reinforce stereotypes that indicate boys are weak if they cry or feel emotions. He says “I think that we have to be careful in how we talk to our boys and be more sensitive in how we talk to our boys. We want to teach boys to have the full range of emotions, let them cry, let them experience their feelings.”

What are some positive ways to teach our daughters and sons about this dangerous aspect of their world without instilling fear or shame?

Maybe surprisingly, the best options are not specific to sexual trauma but to raising healthy children in general. Healthy, strong kids become kids who resist becoming statistics.

Be Straightforward About Their Bodies

Call their body parts what they are and talk about them like you would any other body part. Parents who are too nervous to say words like “penis” and “vagina” make kids feel there is something inherently shameful about their private parts.

My own mother made me feel embarrassed to even come to her to talk about menstruation. No way I was going to talk to her about what was going on sometimes in our own home.

You wouldn’t call their eyes their “see-sees.” You aren’t ashamed to talk about their hands. So don’t make them feel some parts are unspeakable.

Later, if someone tells them not to talk about being touched there, they likely won’t. They’ve been conditioned to believe, “we don’t talk about those parts of our bodies.”

One study determined that after children were taught correct body language, they were more comfortable reporting abuse. They felt the people who taught them the language were safe to talk to.

According to sexual violence prevention educator Kate Rohdenburg, when parents get angry or ashamed of body part language, “children are more likely to think their questions will get them in trouble. This shuts down communication, reinforcing the culture of secrets and silence perpetrators rely on for cover.”

So talk honestly. Openly. Accept that they might ask questions in front of others and that’s OK. Treat it like talking about their arms and legs and they’ll grow up knowing no one should tell them to keep secrets about their bodies.

Treat Children Equally in Play

From the start, girls are often given toys that emphasize caregiving, beauty, and quiet play. There is nothing wrong with these, but balance them out. Make sure girls have access to building toys, hero role playing, rough play, and outdoor toys. Our girls loved their Barbies, but they also thrived on science kits and art projects.

From the start, girls are often given toys that emphasize caregiving, beauty, and quiet play. There is nothing wrong with these, but balance them out. Make sure girls have access to building toys, hero role playing, rough play, and outdoor toys. Our girls loved their Barbies, but they also thrived on science kits and art projects.

And it’s the same for boys! Many boys love dolls, books, cooking, and other activities we would consider “domestic.” Professor Jennifer Shewmaker suggests, “Giving boys the chance to explore nurturing and connecting with others opens up opportunities for them to build important life skills.”

Girls, in particular, understand from an early age by the “traditional” ways they play and the toys they play with that their role is the passive, quiet one who takes care of people and looks pretty. That’s not a good mindset for them when approached by a predator. They may even have been conditioned to believe they have to care for and be concerned about the feelings of the person trying to harm them.

A Brigham Young study suggests that solely traditional “girl” toys and entertainment reinforce stereotypes, which can lead to increased vulnerability. Girls who wrestle, build towers, play superhero, and catch baseballs—as well as play with dolls—have diversified their ideas of “what girls do” and are therefore more likely to see themselves as strong and assertive. Boys who do both have a stronger sense that who they are is OK—and confidence is one thing predators steer clear of.

Speak Careful Values for Your Child

This is particularly important for girls. We still need to be careful what stereotypes we are promoting to our boys, but most of those reflect powerful and active roles in society. Our daughters, on the other hand, receive quite a different message.

I remember when my five-year-old was watching me put on makeup one morning. She asked why I put that stuff on my face.

“To make mommy look beau—“ I stopped. I could not tell my little girl that women were not beautiful without makeup on their faces. What kind of message was that going to send to her little curious mind? “Um, because I like the way it looks and it’s fun. But I also like the way I look without it just fine.” Maybe I didn’t believe that just yet, but I realized I had to for the sake of my three little girls.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with telling our girls they look beautiful. But too often, we convey that as the primary value for a girl. It’s easy to do. Scores of women have been raised on girls’ shopping trips and spa days—fun activities that nonetheless teach girls that clothes, nice nails, and perfect hair are the most important things in life.

I’m not dissing shopping and mani-pedis. I’ve consumed my fair share with my daughters. But I want to be careful I don’t teach them that this is the mecca of womanhood.

Believing that translates to a girl who can be easy prey if someone tells her she’s the prettiest girl he’s seen. If her identity is tied up in how she looks, she’s going to be attracted to the man who begs, “I only want to take your picture because you’re so beautiful.”

Tell her she’s beautiful. Also tell her she’s creative. Smart. Strong. Thoughtful. Kind. Capable. Assertive. Take her for a mani-pedi, but also take her to the astronomy museum. The soccer game. The car show, and the science center.

Teach her that beauty is great, but it is not superior to any other attribute, and it is not her identity.

Talk About the Media They Consume

With three girls, you can imagine how many Disney Princess movies we’ve enjoyed. I can only imagine how many superheroes movies my friends with sons have watched. You’d also probably be able to hazard a guess at how many princess birthday parties we threw and how much pink glitter still resides in my house, though the girls are grown and (almost) gone.

With three girls, you can imagine how many Disney Princess movies we’ve enjoyed. I can only imagine how many superheroes movies my friends with sons have watched. You’d also probably be able to hazard a guess at how many princess birthday parties we threw and how much pink glitter still resides in my house, though the girls are grown and (almost) gone.

While they enjoyed the princesses, and so did I, I made sure to talk about the other movies where girls did not wait for their prince to come. I emphasized the bravery of Mulan. The loyalty of Simba. The intelligence and self-determination of Belle.

So much of programming aimed at girls assumes that their one goal in life is to be pretty or interesting enough to find a boy and keep him. Again, this teaches a girl that any romantic or sexual interest they attract is positive. That’s their role, right? To attract male attention? And when that attention turns frightening, they feel like it’s their fault for attracting it, and so they don’t tell.

Boys who consume superhero movies with only male heroes, as well as increasingly violent programming and games have two problems. If they’re the kid who never sees himself as a hero—never the strong athletic one who can save the day—they are vulnerable to victimization because they think they almost deserve it.

On the other hand, more assertive boys can believe from their media that girls are “accessories” to tough men—also a terrible outlook on gender relations.

Make sure girls consume empowering media along with romantic fantasies. Have your boys sit down with romantic movies too, and give them a good diet of movies with women in strong roles. (Yes, I absolutely swooned over Wonder Woman last year!)

Talk about what they see together. “What did you see him do there? Was that OK? How do you think she feels? Why do you think she’s really doing that?” It might feel odd, but you’ll have some good conversations.

This might even cause us to examine some of our own media choices, mom and dad. How many times did she say “No,” in The Notebook, but he wouldn’t leave her alone? How are women treated in that favorite adventure/thriller of yours?

Teach Your Girls To Set Boundaries and Teach Your Boys to Respect Them

“Girls often get the message that to be liked they have to be nice and accommodating and pleasing. This, Dr. Stephanie Dowd explains, results in ‘a struggle to feel like we’re deserving of our boundaries, especially when someone is questioning them.’ It’s important to help girls understand that they don’t owe anyone attention.”

Give girls the language they need to assert their personal boundaries. Practice with them. “I don’t like that.” “Stop now.” “No!”

With older girls, practice how she’ll talk to a boy who’s being pushy. “I’m just not interested.” “I’m not comfortable doing that.” “Please leave me alone.”

Help them to assess how they feel in situation and trust their feelings. Do I feel good or bad in this situation? Comfortable or uncomfortable? Am I doing this because I want to or because I’ll feel guilty if I don’t? Am I trying to make someone happy, not to appear mean, or not to get someone mad by doing something I’m uncomfortable with?

It’s not a girl’s job, though, to make a boy or man respect her. That needs to be taught early to the boys. Small things like modeling that dad does equal work around the house and treats mom with respect instill this understanding.

Talking about boundaries and empathy can start young. “How do you think she feels that he made her play a game she didn’t want to? What do you think he should do when she said no? Who is your favorite female movie hero?” All this helps boy learn how women should be treated fairly.

Let children know they make the boundary choices about their bodies. As a pastor, I am constantly in contact with children and the families. We’re a “huggy” church, so it’s not uncommon for me to offer a hug to a child. If the child hangs back, the embarrassed parents usually tell her or him, “Come on. Don’t be shy. Give the pastor a hug. You’re being rude.”

I don’t agree. I get eye level with that child and tell him or her, “You do not have to hug me or anyone else. Your body is your own, and if you don’t want a hug, I respect that. It’s perfectly OK, and it’s your choice.”

The parents are surprised, but usually they get it and are thankful. It’s not the end of the world if Aunt Melba is refused a kiss or Cousin George does not get his bear hug. Your child isn’t being rude—she’s setting boundaries of what makes her comfortable.

Silently applaud that while you explain to Melba and kiss her cheek yourself.

Your child is much more likely to tell a stranger, or, let’s be real, Cousin George, since most abusers are family members or acquaintances, “No. Don’t touch me.” She knows her choice is to be respected.

Allow Them To Have Strong Feelings

I remember telling my mother once that I hated her. It was a horrible thing to say, of course, but fairly normal for a kid. My mom put me in a chair, turned it to the corner, and left me alone for at least an hour.

We never spoke about it. But I got the message. We don’t get angry or express our feelings.

Not being able to talk about feelings made me a target for abuse. If I knew my parents were uncomfortable with feelings, how could I ever tell them about something as awful as that?

I don’t mean we let our children scream at us. But we do allow them to disagree, get angry, voice strong opinions, and even say no when it’s important to them. This isn’t disrespect—it’s teaching respect for everyone. This is especially important for our daughters.

“Raising a powerful girl means living with one. She must be able to stand up to you and be heard, so she can learn to do the same with classmates, teachers, a boyfriend, or future bosses,” says a PBS parenting article.

“Raising a powerful girl means living with one. She must be able to stand up to you and be heard, so she can learn to do the same with classmates, teachers, a boyfriend, or future bosses,” says a PBS parenting article.

Teach your children early that they have a voice, and it’s good to use it, even with you.

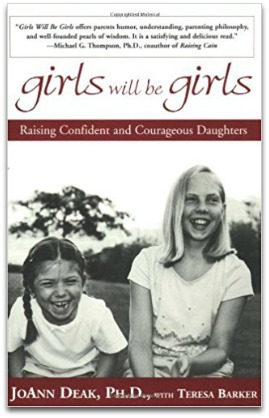

Encourage Them To Take Risks

Many parents take it for granted that boys will run out and try new things and try to build things like catapults or soap-box derby cars. Historically, girls have been encouraged to take a “safer” path. But I say, let them both take risks.

If she wants to build that tree house, or sign up for the 5K obstacle run at school, sled down that scary hill, or go down the tall slide, hold your breath and say, “You can do it.” (Though she’ll need help with the tree house.) If she doesn’t want to, encourage small steps until she can. Try a small hill, a play fort under the tree, an obstacle course in the backyard.

Physically taking risks gives a girl courage to face other risks and a belief in her own ability to handle difficult situations. Girls who don’t take risks have lower self-esteem, according to JoAnn Deak, author of Girls Will Be Girls. These girls are more likely to be prey to males who know working a girl’s sense of self is the key to their success. A girl with a healthy sense of who she is and what she wants (and doesn’t want) will be avoided by predators, who look for the easy catches.

Physically taking risks gives a girl courage to face other risks and a belief in her own ability to handle difficult situations. Girls who don’t take risks have lower self-esteem, according to JoAnn Deak, author of Girls Will Be Girls. These girls are more likely to be prey to males who know working a girl’s sense of self is the key to their success. A girl with a healthy sense of who she is and what she wants (and doesn’t want) will be avoided by predators, who look for the easy catches.

Of course, now mine want to go paragliding and race car driving. So, there is that risk of “if you give a girl a cookie.”

Keeping our children as safe as we can (there is never any guarantee) from sexual violence isn’t a matter of telling them what not to wear and where not to go. It’s not negative things like telling them to cover up their bodies (a sure way to make them ashamed of the bodies and thus more likely to be a victim). It’s not ever giving them the idea that being victimized is their fault or that they could have prevented it.

Common practices don’t work because they put the responsibility on the child—where it never should be. That’s why developing a child who is less likely to be targeted is a better way to go.

Please don’t take any of these ideas to mean you’ve done something wrong if your child is victimized. Maybe you’ve made mistakes. But only one person has done something wrong—the perpetrator.

Helping our kids not to become #MeToos feels daunting, to be sure. There’s a whole culture we can’t control. But we can send strong girls and boys out into it, kids who know they have a voice and a choice, because we taught them so from the very beginning.

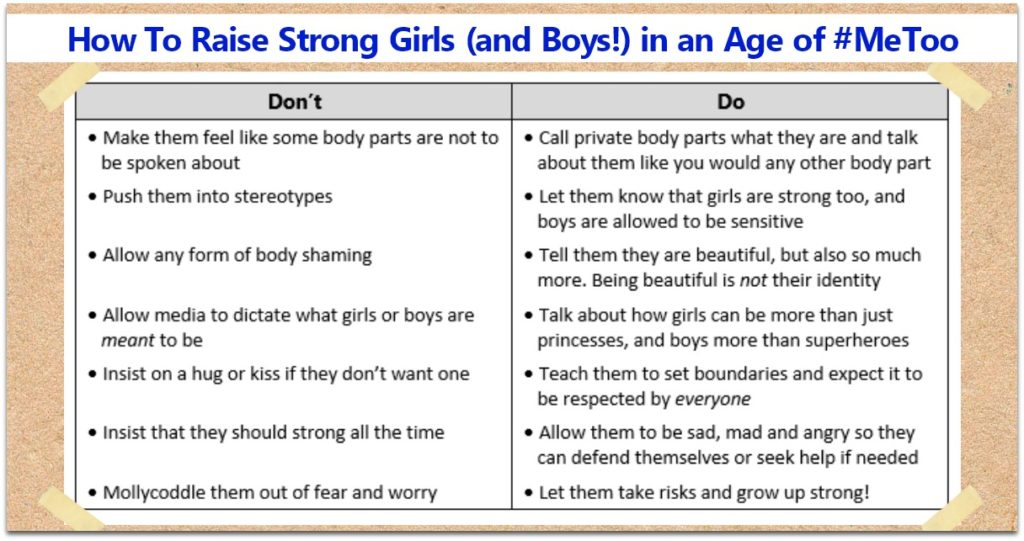

Free Printable & Shareable Summary

(For printing, right click on the image above, choose “Open image in a new tab” or “Save image” and print. For sharing, just share the article link and it should automatically pick up this image.)

2-Minute Action Plan for Fine Parents

For our quick contemplation questions today consider these:

How comfortable are you taking about body parts and sexual issues? What made you that way? How might you gently help yourself to change, if you are reluctant to talk about these things?

Have you made clear to your child that you are a safe place for any information and that they will never get in trouble for telling you anything? How can you do that, naturally?

When was the last time you encouraged your child to take a risk and try something new and big?

Ongoing Action Plan for Fine Parents

Look at your child’s playthings and/or activities. How diversified are they? if need be, find one toy or one class this week that your child can engage with that she enjoys but that is not stereotypically for a girl.

Watch one movie or show together. Talk about the female characters, how they were portrayed, and how male characters related to them.

Read a book together about these issues. Some great ones are My Body! I Say What Goes!; Your Body Belongs to You; No Means No!; and Body Safety Education.

This article fills me with such joy and inspiration! I’m not a parent (yet!), although I do work with kids, and it’s my hope that they grow up to be strong and safe and resilient, knowing that they don’t have to feel like victims of their own bodies or gender norms society expects them to adhere to. Thank you so much for this.

I’m sorry I missed your comment! You are doing such important work. Thank you for it.

Fantastic, Michelle. It is so wonderful to realize we don’t have to be stuck where we started. I am proud of you for forging a new path, and I am grateful for your kind words.

Amen, Anne. Totally agree. Thanks for your supportive words.

Thank you for sharing this honest, brave article to help other parents! I have a 5 year old daughter that I’m trying to start these necessary discussions with, early. With trepidation, I have started naming her parts correctly and answering her questions 🙂 I unfortunately, had parents who sent the message to me, that much of a females worth resides in her beauty and size. Sad 😔

I’m trying to send a vastly different message myself!

This is an important article – thank you! I totally agree with the approach of helping children to understand their inherent worth, so that they have confidence and are less likely to be victimized.

It is important that parents role model total respect for everyone, so that no one is ever objectified – the prerequisite for developing a bully, a predator or a victim.

Amen, Anne. Totally agree. Thanks for your supportive words.

Thank you for the article! I’m raising a girl and a boy and I’m doing my best to raise them basically the same way. There are gender differences (he is already at 15 months a total agent of destruction in a way my oldest daughter never was) but he also likes to play in her kitchen, and play-sweep the house. And they both live to play in the mud and run around the house throwing footballs at each other.

I DO have a hard time calling their private parts what they are!! I’m going to work on it though. It’s uncomfortable but I recognize it’s important. Thanks again!

So did I, Ange. We all have something that’s just hard. Also, I have so many pictures of my girls covered in mud. Sounds like you have a fun household!

I appreciate this article. I too was one who my mom never talked to me about menstruation and sex and the body. My oldest doesn’t hold back and talks to us frequently if something seems wrong physically and asks questions and basically the exact opposite so even though it’s still foreign forme for her to open up about these things I never have to wonder if someone touches her inappropriately or says anything out of line and her not tell me or my husband about it. She didn’t get that from me but nevertheless I’m glad and it taught me to change how I raise our 7 year old through this movement. Thank you also though because I have a 4 year old son and haven’t known how to respond to the me too movement with him and what I need to do different that he not become a victim. Much needed

Thanks, Courtney. It means a lot to hear you have help for your son now. I didn’t start out as the mom who could talk a out such things–ask my kids! I’ve had to learn slowly.

I loved so much about this article. Thanks for sharing your experience bravely.

I have a different opinion on this statement, however: “It’s not negative things like telling them to cover up their bodies (a sure way to make them ashamed of the bodies and thus more likely to be a victim). ” I don’t think teaching girls to dress modestly because their bodies are special need be at all equated with being ashamed of their bodies, and it certainly doesn’t increase the likelihood that they are targeted. I feel it’s quite the opposite. When we model or allow our girls to dress in ways that show off their body as a way to attract attention, we are reinforcing that beauty is their primary allure and that attraction to their body is of primary importance.

Thanks, Anne. I think what we’re talking about is a difference in motivation. Telling girls that their bodies are to be respected, and therefore they should dress self-respectingly as you suggest, is not bad at all. Self-respect aids the confidence that is key here. Not dressing to attract attention is part of this, and I totally agree that girls should be taught that getting attention for their bodies is not their goal. I would add that is a good rule for both genders and girls should never be singled out.

It’s when we tell them to cover up because they are tempting boys or they should be ashamed of not being “covered up,” (and that is such a subjective idea depending on culture), we are also telling them their bodies are bad and if someone preys on them, it’s their fault. They do get that message–I’ve talked to dozens of women who have suffered from it. It’s all a matter of that “because.” Why are we telling them to dress a certain way? That’s what matters.

Hi Jill,

I loved this article. It resonated with me in many ways. I have a nine year old daughter and recently she celebrated her birthday at K1 speed, which a go-kart racing place. She has never been a princess for Halloween till now. 🙂 But I agree with you when you say that it is very important to instill the right values in girls and boys if we were to make our kids strong. I really appreciate you sharing this article. Thank you Sumitha for bringing this article to us.

Thanks, Sandhya. I loved go carting as a kid. I got kicked out of the place once for being too competitive. :0 So glad your daughter has a well-rounded sense of who she is and what she likes. Thanks for the comment.

I love this article! Thank you for writing it! And thank you, Sumitha, for offering it to us!!

Thanks, Shiree. I so appreciate you taking the time to comment!