Isn’t it amazing how you turn out to be exactly the kind of parent you swore you would never become?

Isn’t it amazing how you turn out to be exactly the kind of parent you swore you would never become?

Before I had kids, I was pretty sure I wouldn’t ever be a hovering Helicopter Parent. After all, I had grown up running free on my family farm with my brother and cousins, coming home only for lunch and dinner.

But somewhere along the way the wires between trying to be a supportive, positive parent and a hovering, helicopter parent got crossed.

Before I knew it, I’d got a job at the preschool my children attended just so I could keep an eye on them. My son’s teacher started to avoid me at school pick-up because I would “chat” and subtly ask for a progress report or suggestions about what else we could do at home to help him reach his full potential.

Heck, my helicoptering tendencies had sneaked into even the most mundane aspects of our everyday life. At one point, I had a 20 minute safety routine just so the kids could play in the yard. Complete with sunhats, sunscreen, locking the gates to the fenced (of course) backyard, and putting out three reflective cones into the cul-de-sac so cars would know to drive slowly lest one of the children figure out how to undo the lock and make a break for freedom.

And then I followed 2 feet behind them for the entire 15 minutes we were outdoors.

Sounds a bit familiar? Nobody sets out to be a helicopter parent. But, it kind of creeps on you, doesn’t it? Here are 10 more signs.

You Might Be a Helicopter Parent if…

- You only let your child play on playgrounds with shredded rubber mulch.

- The first thing you did when your 4th grader came home crying from school because her best friend Jill called her a name is to call Jill’s mom to sort things out yourself.

- You have found yourself up at 11pm rewriting your child’s English essay because you know that they could have done a better job if they hadn’t been so tired.

- Your 8 year old still has the training wheels on his bike. Not that you let him ride it that often. The sidewalks are dangerous and they go too fast for you to keep up!

- You have a bad back from stooping down and following your toddler’s every step.

- You get heart palpitations at the thought of letting your child go on a field trip with their class.

- Having them help out by preparing dinner or cleaning the house has never crossed your mind. Knives are sharp and the cleaning fluids are too dangerous!

- As a Christmas gift you gave your daycare a webcam so you could watch the daily happenings while you are at work.

- You and your son are having a meeting with the teacher and when she asks him a question you answer it for him.

- Your child didn’t get accepted to his preferred major at college so you call the Chair of the department to negotiate for an exception.

Full disclosure: I am guilty of 5 of these. Okay, 6. The others are all confessions from fellow recovering Helicopter Parents. For number 10, however, I was on the other side of the table with the Chair receiving the parent’s phone call.

My Wake-Up Call

I had always been one of those parents who would race around the playground following 18-month-old Evan to whatever equipment caught his eye. I was terrified that he would fall, and I caught him every time he threatened to topple over.

I had always been one of those parents who would race around the playground following 18-month-old Evan to whatever equipment caught his eye. I was terrified that he would fall, and I caught him every time he threatened to topple over.

Then his brother Henry came along. One day I couldn’t be there to catch Henry when he fell as he toddled along. I saw him lose his balance. I sucked in all the available oxygen around me and braced for a horrible fall.

But what he did amazed me.

He felt himself wobble and he naturally shifted his weight and plopped down safely onto his bottom.

It had literally never before occurred to me that they would have this natural instinct of bracing themselves. I had always expected and assumed they would stiffen and go down like a tree, cracking their heads in the process.

Maybe I didn’t need to be so “on the spot?” Fine. I’ll stand up and follow from 2 feet away. Just in case.

Soon after that incident, we moved to Switzerland where helicopter parenting is almost unheard of, and the social norm is to not “interfere”.

We had been here a month and my neighbor pulled me aside and said, “You know that your 9-year-old can go to the park by himself, right?” She went on to say that the other parents would look at me funny or say something to me if I stood next to him as he played on the equipment.

I went to the park with him anyway. I noticed differences in strength, balance, and confidence with the Swiss children. I noticed he had trouble in resolving disagreements: he blew them out of proportion, expected instant sharing, and didn’t show as much grit and determination.

He was upset and crying because he was so much less able physically than his Swiss peers.

For the first time, I had the suspicion – perhaps my hovering and over-protectiveness was causing more harm than good?

Let’s Talk About What it is to Be a Helicopter Parent

In To Kill a Mockingbird, Atticus Finch says, “There’s a lot of ugly things in this world, son. I wish I could keep ’em all away from you.” It’s like the parents of the late 1990s read that and decided they were going to be the generation that finally succeeds in protecting their child from all that ugliness.

What we forget is that he continues the line with, “That’s never possible.”

Parenting is a nerve wracking proposition.

No one knows what they’re doing, especially with a first child. It doesn’t help that TV dramas and news programs continuously pump nightmare What-If scenarios into our homes and imaginations.

It also doesn’t help that should you actually try to give your kids some freedom, you run the chance that neighbors will call child protective services to report you.

Born out of these fears and worries, Helicopter Parenting is an extremely regimented and directed parenting style with the goal of protecting the physical and mental well-being of the child, sometimes even at the risk of stifling the child.

We’ve all had our Helicopter Parenting moments.

Pacing around the equipment at the park, arms extended like Frankenstein, their first time climbing up and around the equipment.

Helping your toddler retrieve their toy from another toddler who snatched it away. Or at the library trying to convince another child to share a book that your son or daughter wants.

Trying out your best Ninja-Dad impression as you follow your teen through the mall to keep an eye on them.

We’ve all been there.

Why does it matter? Who cares if I’m making weekly chiropractor appointments for my bad back or calling up my son’s teacher on a weekly basis to check on his progress?

The Downside of Helicopter Parenting

A while back, Edward Deci and Richard Ryan published their Self-Determination Theory. According to them, the 3 innate needs that all human beings need for healthy development are:

A while back, Edward Deci and Richard Ryan published their Self-Determination Theory. According to them, the 3 innate needs that all human beings need for healthy development are:

- Basic need for autonomy

- Basic need to be confident in one’s abilities and accomplishments

- Basic need to feel they are loved and cared for

The closer we are to having these 3 basic needs met, the more satisfied we are with our lives.

In 2013, Holly H. Schiffrin, Miriam Liss and their co-authors used this theory to measure the effects of Helicopter Parenting on college students.

They found being too involved or over-parenting in a child’s life undermined these 3 basic needs to different degrees.

They also found a higher degree of depression and anxiety as well as a lower general satisfaction with life. In their words –

Furthermore, when parents solve problems for their children, then children may not develop the confidence and competence to solve their own problems… Our data suggest that a sense of competence may be the basic nutriment most essential to well-being.

As if that weren’t bad enough, Helicopter Parenting can strain the parent-child relationship. As children enter their tween and teen years, they start craving independence and privacy.

How many times have I heard, “Why can’t you just let me do it myself?” and “Moooaaaammmmm!” hissed through gritted teeth when I try to help.

Helicoptering in to save the day can actually cause embarrassment and result in your teen and young adult pushing you away just at the moment you most hope they will want to confide in you.

Even children as young as 2 years old need moments of independence. Remember that “MYSELF!” phase? Boy, I do! That was the worst phase for this helicopter parent.

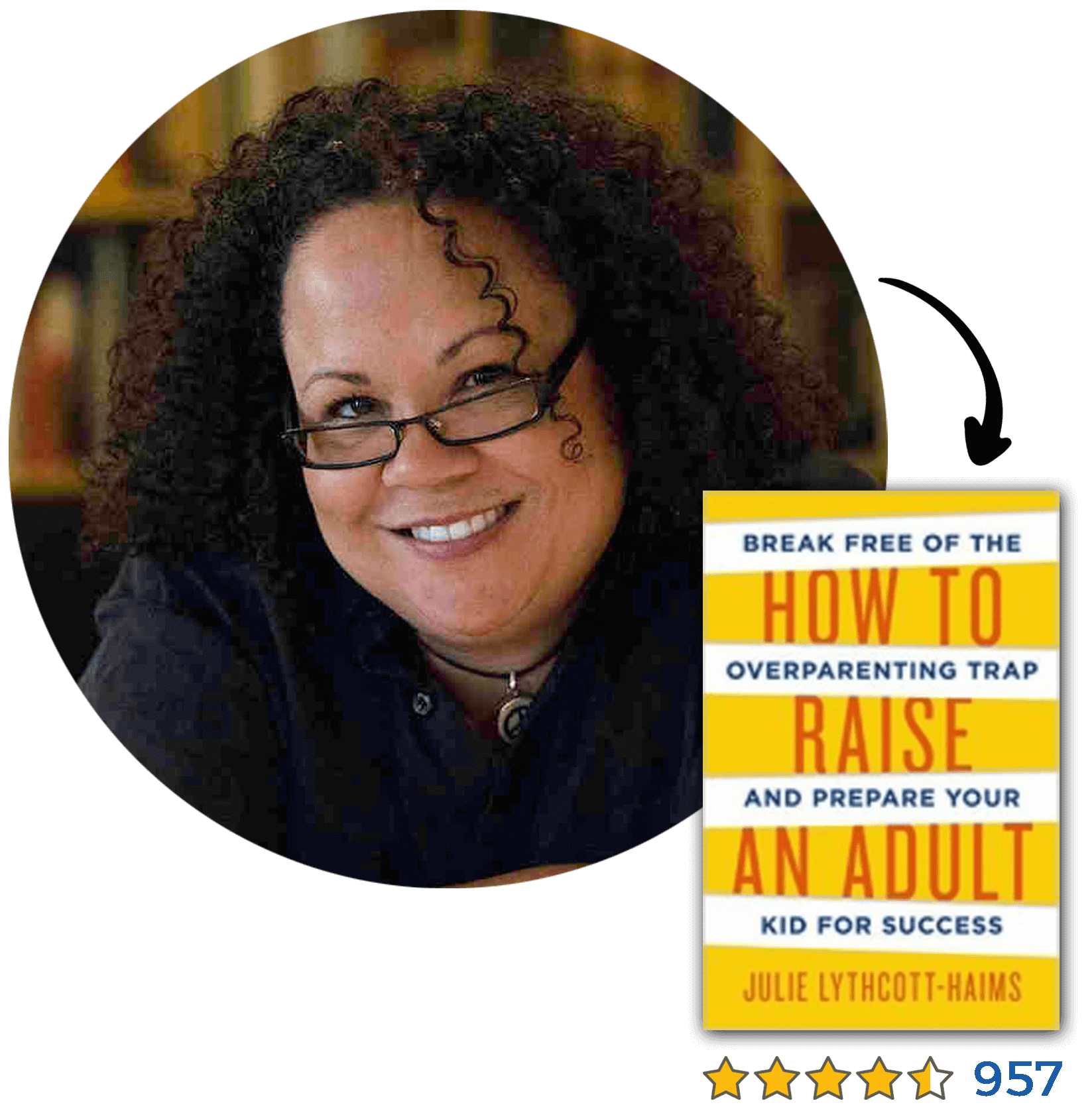

Curious to learn more about how helicopter parenting can interfere with our children developing independence? We partnered with Julie Lythcott-Haims, author and TED Talk motivational speaker, to discuss how we can get stuck in the trappings of helicopter parenting, why it is harmful, and how we can break out of it.

Curious to learn more about how helicopter parenting can interfere with our children developing independence? We partnered with Julie Lythcott-Haims, author and TED Talk motivational speaker, to discuss how we can get stuck in the trappings of helicopter parenting, why it is harmful, and how we can break out of it.

This packed masterclass is one of the 60+ masterclasses you get when you join the AFineParent Academy today. Click here to learn more.

A new study just out in 2015 by Jean Ispa and co-authors in Social Development have found that Toddlers who are given space to explore and interact with their surroundings on their own have a better relationship with their parents. They seek their mothers out for play and interaction more often than do the children with helicopter mothers.

Both these studies concluded: Be available for your child, but let them take steps to come to you.

So how do we find out what is going on with our children and keep them safe if we’re not hovering? This is where all that work practicing active listening pays off. Active listening builds bridges of communication that allow ideas, concerns, and trust to flow freely between you and your child.

How I (Mostly) Stopped Hovering

Like most bad habits, breaking out of Helicopter Parenting hasn’t been easy. But I’ve come a long way enough to consider myself a reformed Helicopter Parent now. Here are a few things that helped me –

1. Take stock. The first thing I did was to look at what I was doing for him that he could and should be doing for himself. I actually wrote a list.

2. Use a realistic, phased approach to stop helicoptering. Once I had the list, I highlighted the things on the list that I would be comfortable with him doing tomorrow; then picked another color for within 6 months; and another color for a within a year.

When I saw the list it was clear that a lot of the things I had been preventing him from doing were about me and not his ability to actually do them successfully. I have to admit that the graduated introduction of these responsibilities was about my needing a safety net just as much as him needing time to adjust.

3. Learn to accept that their work won’t always be perfect. The carrots would not be perfectly cut and his grades wouldn’t always be A’s. I give feedback when asked, but it’s up to him to decide to fix it.

4. Let them fight their own battles. If someone isn’t sharing, that’s too bad. If he has had a falling out with his best friend, that’s something for him to work through. I am still his shoulder to cry on and I will actively listen to coach him through some situations, but (with a few exceptions) it’s up to him to work it out.

5. Let them take risks. There are things he asked to do as his confidence was growing that I felt nauseous about saying yes to.

5. Let them take risks. There are things he asked to do as his confidence was growing that I felt nauseous about saying yes to.

Remember that classic team building exercise where you fall backwards, trusting that your teammate will catch you? You’re all giggly and nervous as you stand there with your eyes closed and then you feel the rush of relief and joy as your partner actually saves you? We Organization Development consultants have you do it because taking a risk and seeing the success that comes from that risk builds trust. Trust provides a crucial foundation that allows you and your team (and families are a team of sorts) to have even more amazing successes.

One day, after weeks of begging, we allowed Evan to take the tram alone. It was only 3 stops and his dad was watching him get on the tram and I was there to meet the tram, but I thought I would have a heart attack waiting for him.

However, the smile on his face when he got off that tram transformed me. Sir Edmund Hillary could not have had a bigger smile after scaling Mt. Everest.

His success made his confidence in himself bloom and it also boosted the confidence and trust I had in him.

6. Let consequences stand. And don’t say they aren’t fair. He came home once crying about the C he got on an essay. I knew how hard he had worked, and I felt equally disappointed, but I had to back up the teacher. If she thought it was a C paper, then he earned the C. I had to let him not like it and have him talk me through what he did well and what he could do better next time.

7. Learn to leave the room. If I feel the need to take over and “help”, I leave the room. I can give one piece of unsolicited advice or demonstration, but that is it. If I feel like I need to do more I literally back away. Also, I allow myself to say “No” when he asks for help, followed by “I think you can do it by yourself.”

8. Journal the journey. Writing things out helps me sort things out in my mind. The impulse to leap in and do it for him is always there inside me. Reading my questions and struggles out loud helps me judge if I have a legit concern or if I’m taking his successes and failures too personally.

As parents, we instinctively want to protect our kids and keep them safe. Sometimes, without quite realizing it, this can lead us to becoming Helicopter Parents. The trick is to recognize when these instincts kick in and to intentionally back off to let our kids learn to take care of themselves.

Because, no matter how much we want to, we really can’t protect them all the time. Might as well equip them to protect themselves the best they can.

The 2-Minute Action Plan for Fine Parents

Time for our 2-minute contemplation questions –

- Do you see yourself exhibiting any of the warning signs that trigger your Helicopter Parenting tendencies?

- Do you act on them or do you tamp down on them?

- Do you just have a few Helicopter Parenting tendencies now and then, or has hovering becoming a habit, turning you into a Helicopter Parent?

- How does your hovering – occasional or persistent – impact your kids?

The Ongoing Action Plan for Fine Parents

Over the next few weeks, pick tasks and responsibilities that your kids can do by themselves, and let them. This list of 50 simple challenges for teaching responsibility could be a good start.

Keep practicing active listening. Active listening is a great safety net for helicopter parents because it keeps those lines of communication open while letting your child feel like their independence is being respected.

Look for calculated risks that your child can take that will boost your child’s confidence in themselves and help build trust. This list of 50 things to do to make your kids street smart can help you get started.

Journal! Journal! Journal! Parenting is a complex and messy business. Getting your thoughts, feelings, fears, and hopes out on paper can help you sort through the messiness and bring some calm and peace to your life.

I was recommended this website via my cousin. I’m not positive whether this post

is written through him as no one else know such exact about my problem.

You are incredible! Thank you!

Thanks for this article. At a point in time (with my 1st child) I may have been one of those helicopter mums 🙂 Yes, it is important to let our children make mistakes and let them learn through them. My mind is more relaxed nowadays. I know it was hard at the beginning but this is the only way our kids could “learn” to be responsible and take accountability for their actions. Great article

Oh my.. who the hell are you to say that to him? I say, if his wife wants a loser for a son, that’s her problem and not this guy’s! He needs to leave because she’s obviously an idiot with no good parenting skills. And btw, I’m a woman writing this 🙂

Oh my.. who the hell are you to say that to him? I say, if his wife wants a loser for a son, that’s her problem and not this guy’s! He needs to leave because she’s obviously an idiot with no good parenting skills. And btw, I’m a woman writing this 🙂

Useful information! Thanks for your great sharing.

You are very welcome!

this article is very helpful for me

I am so glad! Thanks!

Thank you for the information above. I would probably have to revise many things to teach my children again. Thank you for telling me what I should do. thank you

Surely you have a happy life when doing these things. congratulation

Thank you so much for this informational post.

I feel that at different ages we will treat them differently, of course.

But in order to do so, we must know what our children need, in order to help them properly.

This topic is quite new and interesting with me. I use a lot of free time to read the information at your site. Thank you so much for your sharing.

I just turned 14 and although i’m not stupid or irrisponsibl, my parents still treat me like i’m a three year old who is clueless and defensiveless. For example, up until recently, my parents wouldn’t even let me go to the park with my firends (not even five minutes away from my house). My grades are fine, and I still complete my homework and yet here they are thinking 90 avg. is a “fail” and “No uni will accept you. Do you want to end up on the streets?”. I had a friend over and every 10 minutes they’d come in and “check in”. They also think my opinion doesn’t matter at all and I’m just a stupid child. Always pushing and hovering my personal space and RARELY ever letting me spend money that I *worked for*. They need to let me experiment with some things, like clothes, or activities.Worst part is that they refuse to accept they’re not perfect, and don’t want to make an effort to change. I have a sister, and now that shes an adult, shes practically broken ties with my parents, not often eating dinner with us. I can finally understand why. I’m sorry for venting, and I know this is kind of a late reply, but is there any way I could change things? Even if It’s small, just to loosen their death grip on my life, because I’m tired of all this.

*spelling and grammar

Hey,

I’m 27 years old and I have been and still am in the same situation. It’s hard to change your parents’ point of view as their child because they think that they are the adult and they know what’s best. If they can’t see for themselves, you can try to suggest going to family therapy with them. Remember that they aren’t hovering out of ill intention, it just comes out wrong. I want you to know that no matter what your grades are, you are worth it and you are capable.

If you get a chance to apply for exchange or to live with someone else for a while, you should push for it and try it. Show them all the benefits of what could happen. After coming back from being separated, my parents were more lenient on letting me do things on my own.

From my own experience, gaining their trust is really important so being a rebel is not the way to go. If for example they think going to play with your friends is dangerous, introduce your friends to your parents. Show them that you made good friends.

Hope this helped.

Cheers!

I am a book reader so I appreciate the knowledge you share here

Great sharing! Luckily I am not a helicopter parent, but I see it in my friends. I think they need to read your article, will share it with them today. thank you for your great sharing

Thanks for this informative article

Wow! Great Article. Really thanks for sharing this information.

Thank you so much for this informational post.

Parents should learn more on how to care their kids, not just supervise or tell them have to do something. They need to change the way to teach the kids. Sharing more and less enforcing. Nice article.

Totally agree that excessive protecting children is not a good way to help them. Just being there and helping them as they need.

Great article and great contributions too.

I will work things out after realising am already exhibiting helicoptering towards my three year old.

Thank you for sharing!

Thank you for your comment! I am glad this article has helped to give you a wake-up call about how you are parenting. I like to remember that I am there to support, but not to do it for them. 🙂

Wow, it’s a great article. It has a detailed analysis with reference. I haven’t had any kids yet. But it’s helpful to read it. Thanks for sharing.

I am so glad that you are already finding it helpful in informing your parenting style. Thank you!

Thank you so much about this helpful post.

You’re welcome!

That so so amazing for me and my wife.. Thanks for your sharing and wait more infor about this topic!!

You are so welcome!

I would like more information on the the topic of helicopter parenting. I cannot stop myself and am losing friends over this. Please help

Hi Y, Thank you for reaching out.

Firstly, know that you are not alone. Helicopter parenting happens all the time. Everyone does it at some point during their parenting journey.

If you are really having a hard time letting go and letting your kids start taking (minor) risks, I suggest you contact a parenting coach who you can meet with on a weekly basis. They can walk you through some exercises that will help you see that your children are going to be okay, even if they fall.

If even that is hard to do you might be suffering from anxiety like me. Go to your doctor and talk to them. They can help or they can find someone else who can help.

I hope this helps you.

What a great article! As a mom of six, I started out as a helicopter mom in the making, but my wise husband helped me to realize that it was a going to handicap them. Then we had too many children to be able to hover over all of them. I just want to encourage all moms out there that it is much more rewarding to raise a kid that can take of themselves than it is to keep taking care of them. Take this advice and let them grow strong! You will be so glad you did!

Thank you! It can be nerve-wracking, but we can handle it!

Great article and great contributions too.

I will work things out after realising am already exhibiting helicoptering towards my three year old.

Thank you

Appreciate it.

I have an 18 mo old. I’m very aware of helicopter parenting as I was raised by one and am committed to doing things different-but I love and appreciate my mom of course!-

She’s in a little Montessori school. Can I visit/observe one day? Is that ‘helicoptering’?

Thanks,

Maggie

Observing is fine once in a while. Stepping in everytime they try something by themselves is toxic.

Hi accidentally happened to read your article n was shocked to realise to what extent i am a helicoptering parent. I wanted to stop this over protecting attitude whn my daughter completed schooling &discussed about it with her too. But whn she reached college again seeing her struggling with studies forced to step in with help or else she will fail n her internals..i realise that she has become less confident even to take his own decisions bcoz of my parenting..is it too late for me to come out of it?? How can bring back the confidence in my teen kids…pls help

Great Article…will try my best to learn and adopt…keep up the amazin work…

So, this may be a new one for you all, but I’m actually a child of someone who shows some helicopterish tendencies. I am socially autistic (meaning I ha have a hard time working and making friends with people of my age group, but older/younger people I have no problems with) and have ADHD. My dad lets me sink or swim under my own power, only stepping in when he feels that the proverbial warship of my life is taking on WAY too much water. My mother on the other hand, will range from a similar attitude, to being able to put the majority of helicopter pilots to shame with her hovering technique. Things such as constantly talking with teachers, constantly checking my grades, having her BusRoute app open in the morning until I call her from school, or text, or asking the district for a 504 plan, even though I feel like I don’t need it and it would be a waste. She also constantly hovers over my use of technology, which has made any attempts at starting a YouTube channel, owning a smartphone, or just owning a computer that I can call my own, that no one else can touch, a right pain and uphill battle against relentless machine gun fire (so far, I have only ever managed to own the computer, and even then, it broke soon afterwards). She’s also very strict, to strict at times, about the games I can play, and any game that’s rated T (for teen) a battle, avena though I am 15 years, soon to be 16, and even owning game that are rated M (for mature) difficult, even though I have played several, and am unbothered by content. She has a hard time letting me do new things without her knowledge and approval, as well as supervision. She believes that if, even for a second, she stops hovering over my grades and schoolwork, I will fail everyone of my classes, which, while I might struggle a little, is honestly untrue. I’m worried that if I’m not allowed to stand on my own two feet and do things my way, make my own decisions, about either games or schoolwork, I may not be ever able to leave my mother’s sphere of influence.

And I know that there has been many discussions about children and technology, but at age 15, I should be allowed much more independence, so I can get used to it. The cell phone, or, in my case, a computer of one’s own, is the first true sign of independence from a parent. I have recently received a flip phone, and while this is a start, I would like much more freedom, freedom to Snap my friend, or just listen to music without having to ask my mom if I can borrow her phone, thus feeling like a 4 year old. My mother is also very worried about letting me learn to drive, and constantly says “maybe when your just a bit older”. Helicopter parenting, at least for me, is frustrating because it means a lack of independence from my parent, and having to rely on them. I love my mom, truly I do, and don’t want to instantly put up a shield wall to her help, as I believe some of it is warranted, but she focuses to much on certain things, like keeping me from doing something, or trying to help when I’m frustrated, even when it’s hopeless.

Same. Kind of autistic ( ted. )

Mom jumps in everytime i try to do something and blame me if not permission were asked… Fucking shit. I can exist without you!

I think there NEEDS to be a happy & healthy middle ground. I have had seen MANY “free range parents” sit back and allow their children to pound the crap out of another kid on the playground and bully – because it’s better to let them “work it all out themselves”. Or those “free range” narcissists, who are too preoccupied with their own affairs than to know that their children are uprooting all the flowers out of the neighbours’ garden. I have seen ALOT of that! “Let the kids work it out themselves”, is really fine and dandy when it’s your kid throwing the punches I see… This “figure it out yourself” style of parenting is not exactly preparing kids for the real world either – maybe for the judicial system…? There is huge problem with parents that don’t TEACH THEIR CHILDREN boundaries & to respect other human beings in the name of “free range parenting”. Parents do need to step in and “helicopter” their “sweet heart” from pounding another kid on the playground & being disrespectful everywhere they go. To think that is ok is barbaric! I have also met “free range parents” who homeschool as well, where they don’t even teach their children to read, write or the basics of Mathematics – “Just go learn for yourself”. From what I have seen about “free range parenting”, it is NOT exactly preparing their children to be DECENT citizens of this World either… Like I said, there is a happy & healthy medium ground.

What an excellent post! In fact, a school social worker (Elgin, IL) loved it so much that she shared it as a tip for other teachers and parents on the AN10NA app so that’s how I found it. Your tip can be found under the Parent Connect icon – Topic: Ap*parent* Dilemmas but please check out all sorts of topics, review tips, and post some of your own.

Download the app for free using the links on our website http://www.AN10Na.info and please help spread the word 🙂

I let my mother in law babysit for the first time(I’m the mom that is relaxed about most stuff.when my 4yr is climbing and it’s high I’ll stand behind in case but let her do the work.Let her fall provided it not on glass.)I don’t see myself as a helicopter mom however as I do with anyone watching my child explian what I want for her while in someone else’s care.She has been judged and always comparing me and my daughter to her kids and other grand kids.and this time I had two things no sugar due to events the night before and the following night.(and her serving sizes are that of an adult.not needed)Second thing was about the potty as she’s not completely trained.and said told daughter to tell you and all you have to do is help wash hand she can do the rest.and that’s when she was so offended.”you know I raised 3 of my own habe you head of being a helicopter mom.And this pissed me off lots.I explained I do this with my parents to don’t take offence. then had fight with the

Bf.who spent take my daughter out any were spends a few hours a day with her aides with his mom.and that’s dumb because there aren’t side to be taken.I did nothing wrong.Thanks for letting me rant…

I have a very unusual opportunity as a gramma to watch 2 completely different parenting skills at work. My Stepson and his wife are complete helicopter parents! My daughter is more a parent like I was…. allowing her kids to take the tumbles necessary to learn and grow. My stepsons daughter is 20 months old and walks like a 1 year old. She stumbles over the smallest obstacles and wont attempt to climb on anything. Once she was not watched going down the stairs (padded and carpeted) and she tumbled down 3 steps. The wife yelled and scolded her husband for not being behind her on the stairs! It was an ugly and chaotic scene! He was completely beaten up for it! He has never let her out of his site since and she cannot walk down any stairs alone yet and can only crawl on hands and knees, up the stairs at 20 months!!! She is overweight and clumsy and fearful. I have watched her go from a fairly sociable baby to a withdrawn and serious toddler who laughes very little. She was NOT always like that. My daughters daughter is 19 months. She can go up and down the stairs alone. Runs, bounces in the bounce castle alone. Laughs plays and jabbers joyfully all the time. She rarely trips, she is a confident climber and can climb anything. Now mind you, this presents its own set of challenges as there is NOTHING she can not get if she wants it. She can open any door, climb into any chair, move a chair to a location that has whatever she wants. Yes my daughter has to be especially vigilant because that kid has learned to be quite independent. So here I am as gramma to behold this little experiment of two completely different parenting skills. Its very interesting. One little side note. My stepson was raised by a helicopter mom. Very controlling and he never learned to do anything for himself. He is completely dependent on us. He has never worked in the real world. He married a woman just like his mom, a control freak and is hen-pecked to death. I just hope they dont ruin their kids the same way he was ruined. Dont see how they wont but… time will tell…

I should add about the stair incident…. the toddler was 19 months at the time of the first tumble and this was the one and only time the husband was not vigilantly walking behind his daughter. And so in conclusion…the toddler, when allowed to finally tackle the stairs alone, could not, and watched her father be emasculated right in front of her because of it! Kinda sad!

My 13 year-old stepson is still unable to do the following:

_ know his house address

_ ride a bike

_ ride the school bus

_ make a bowl of cereal or oatmeal or use the toaster

_ clean out his school backpack

_ know the difference between states and cities

My wife just shrugs her shoulder and says, “Oh well”. At this rate, he will be living in our basement at 20, smoking pot and playing video games until 3 am and sleeping in til noon.

Ohhhh boy, sounds like you’ll have a bad time. Perhaps it’s not too late to change your son. But I’m 16 so what do I know about parenting?

Ordinary paternal dislike for his male offspring. It is easy to hate him especially because it’s not your child. However, instead of sharing your problems with the whole freaking world, you could talk to your wife and child in a calm and kind manner.

Oh my.. who the hell are you to say that to him? I say, if his wife wants a loser for a son, that’s her problem and not this guy’s! He needs to leave because she’s obviously an idiot with no good parenting skills. And btw, I’m a woman writing this 🙂

I never thought I’d be a helicopter parent, but I was with my first, a little less with my second, and not at all with my third. Maybe I tired out. Maybe I felt more comfortable being a mom. My first child is in HS and has responsibility issues and has a hard time with failure. My third child has none of that. I wish I can go back and do a re-do with my children, but all I can do is commit to changing how I parent them from now on.

Hi Paly, What you said is one of the primary founding principles of this site… I was a very impatient parent for the first few years of my child’s life, and wish I could go back and change that. Since that can’t happen, the next best thing is to make sure that here on forward we do the best we can to be more connected, aware and intentional parents. HS is not too late… stick with your commitment and by the time your child has to leave for college, you will see the benefits of more connected, positive parenting. Wish you the very best!

HS is NOT too late at all. It’s a perfect time for you and your oldest to practice trust exercises along with active listening. Have a conversation to prep them that includes your expectations of them and let them tell you what they expect/need from you. Decide together on things, tasks, and responsibilities they can take over and then journal through the journey to stay conscious about when your impulses to jump in and help are strongest. Definitely keep up the communication so you two can keep thing going in the right direction. You will be surprised how quickly their confidence and independence will grow!

This is a great article! I love the practical tips and I think it is so great to see that you aren’t just preaching to the choir–you’re living it. For your ’10 signs,’ I’d love to see different lists for different age ranges. I think that helicoptering looks different at different ages. You did a great job of trying to incorporate them all, but it would be nice as a follow-up to see this broken down even more by age. Working with young college students, I see the impact of helicoptering daily.

Thanks for your kind words, Jennifer!

And I like your suggestion about breaking up by age… we’ve done a few articles before where the discussion was broken up into sections based on the ages of the kids and they were well received. I will keep this in mind as we get the future articles ready(I’m the site editor btw, in case you are wondering 🙂 )

Excellent article, just when I needed it. Wake up call for me that probably I was going that way and it’s time to let go now.

Thanks for your kind words, Ekta. Good luck with letting go. It’s not easy, but oh-so-necessary!

Great post! I never saw myself as a “helicopter parent,” but now that my kids are older I notice how much more relaxed parents of younger kids are than I was. It’s a bit of a chicken and the egg question — are they more relaxed because their kids are more confident, or are their kids more confident because they’re more relaxed? 🙂

I agree with your recommendations, and I wish my kids’ childhoods had been more like mine. By a certain age, my brother and I had free reign, as long as we were home before dark. 🙂 It was a great way to grow up.

Thanks for the kind words, Stephanie.

I coudn’t have said it better — it certainly is a chicken and egg problem of whether we need to be more relaxed first or the kids need to be more confident. What I have noticed though is that, it works in our favor… if I can bring myself to relax just a little, my daughter’s confidence improves just a tad bit, which makes it easier for me to relax a little more and so on. It’s been a nice way to break out of my latent/occasional helicoptering tendencies 🙂

That’s a good point, Sumitha. There is a gradual give and take. I’ve been trying to do this with my eleven-year-old, who is temperamentally quite cautious. I’ve been working on relaxing my approach and encouraging her to take more risks.

My mother is like that, nd it been eating up self-esteem, how do you get them to back off. Every time I make a mistake, it’s an opportunity for her to criticize how I’m not ready yet. Then I feel like I have to be perfect and it’s all out of fear! I hate her for it. Then she gets all philosophical the next day and says, honey, you look really stressed… is everything all right?

She like that with everything! Including LAUNDRY.