Amelia is having a problem.

Amelia is having a problem.

I can tell from across the room, where I’m addressing another student’s question about their circuit project. Her face is getting redder and redder, her eyes are starting to get puffy, and she’s breathing very fast.

Amelia is eight, and every problem is the biggest problem of her life—even one as simple as a broken bit of copper wire.

I know what will happen next—if she doesn’t get to replace her wire right now, she’ll start to scream and sob uncontrollably. She might get out of her seat and throw her project materials on the floor.

In short, she’ll lose it and create an intolerable class disruption, all because her emotional response to momentary frustration is crashing out of control.

I’m worried for her, because unlike a broken wire, this emotional cascade can wreck her experience of school and jeopardize her future. Her panicky reaction to perfectly valid feelings of frustration can lead to behavior issues with real academic consequences.

Except today, Amelia takes a deep breath.

She slows down her breathing, and though I still see the edge of tears in her eyes, her face starts to return to its normal color. She puts up her hand and waits for me to call on her.

“I’m frustrated,” she declares. “My wire broke, and I can’t finish the circuit.”

“What can you do to fix it?” I ask her.

She thinks. I give her some time, letting the silence spool out for a minute or so. I see her frustration begin to shift into curiosity. She’s fidgeting with a bit of the aluminum foil we’ve been using to make very simple switches.

“If I wrap the pieces of wire together with some aluminum foil, will it make them work?”

“That’s a cool idea, Amelia. I like the way you’re thinking. Please try it and let the class know how it works, because I bet someone else will have the same problem and you could help them.”

Amelia is excited to have something to contribute. She has in fact found a workable solution—not the most elegant, but one of her own design.

Two weeks ago, this exchange would have been inconceivable.

I’m an engineering teacher to elementary students in an innovative independent school.

At my school we have seen how making and tinkering can help kids like Amelia develop better skills for dealing with frustration. Even if they never think about how circuits work again, if they can cope with setbacks effectively, they will have gained an incomparable skill for dealing with the challenges of life, both in and out of school.

I’m beginning to use what I’m learning here to help my own child cope with frustration, too.

We have all dealt with frustration in our lives. We each developed different coping strategies for getting through frustration. Some of these coping strategies genuinely help us, and some hold us back, or worse, destroy our lives and relationships.

You can probably recall a time when your coping strategy for dealing with frustration, whether at school or work or at home, created a huge problem for you or made an existing problem worse. We all know someone whose learned responses to frustration include throwing or breaking things, shouting at people, or other destructive behaviors.

While frustration can be a cause of aggressive behavior in healthy children and adults, frustration itself is normal—and in fact necessary to learn and grow.

The poor coping strategies our children may have developed to deal with frustration can be unlearned and replaced with more effective skills. By doing so they can capitalize on frustration to accelerate their learning.

Tools for Dealing with Frustration

As parents and educators, we can show our kids how to use a set of simple tools to conquer frustration.

I also get frustrated in class sometimes (okay, a lot!) and I use those frustrated moments as opportunities to model the following techniques. I also explicitly talk about them with the students, and I’m transparent with them about my goals in teaching them to deal with frustration.

Our kids need both—modeling and explicit teaching. If you have a kid who is having a hard time dealing with frustration, put these strategies to work for yourself, and share them with your child.

1. Banish “I can’t…” unless you follow it with “…yet”

Nobody was born knowing how to do everything. Just about everything you know how to do, you learned at some point.

Nobody was born knowing how to do everything. Just about everything you know how to do, you learned at some point.

Before you learned it, you couldn’t do it, and now you can.

Unless what you’re talking about is physically impossible, such as breathing underwater or walking through a solid object, you can only say truthfully that you can’t do it right now.

Watch your own speech for this tick when you’re frustrated and correct yourself every time you hear yourself say “I can’t.” “It’s too hard (so far)” and “I don’t know how (but I can learn)” are other good substitutions to make.

2. Make frustration a friend

I tell my students that frustration is a signpost saying you’re almost there. You’re about to have a breakthrough if you just keep working on it a little longer.

Frustration says, “Use your tools—that eureka moment is close!”

If you’re not getting frustrated at all, your project is a little too easy for you and you’re not learning as much as you could be. On the other hand, if you’re experiencing the amount of frustration you can cope with, you’re right at the sweet spot of difficulty for your learning.

3. Notice and describe what’s happening

When Amelia said, “I’m frustrated,” she opened a pressure release valve on her emotions. I could see her visibly relax.

When she explained why she was frustrated, just like I’d taught her, she avoided blaming language and simply stated what had happened and why it was frustrating.

Crucially, I didn’t respond to this by accusing her of being careless—it doesn’t matter why her wire broke, just how she planned to solve it.

Respond to your child’s explanation with a calm and optimistic question, such as “What have you tried so far?” and “What are you going to try next?”

Avoid jumping right in to do it for them.

4. Know when to take a break

When you find yourself trying the same thing repeatedly even though it isn’t working, it’s time to take a break. Work on a different part of the project, or step away altogether.

When you find yourself trying the same thing repeatedly even though it isn’t working, it’s time to take a break. Work on a different part of the project, or step away altogether.

The key is to commit to come back to work on it in a few minutes—I find ten or fifteen minutes is usually enough to reset my brain.

When you return to the task, you’ll usually find you have a fresh idea for a different approach.

5. Change your perspective by telling a story

Describe what’s happening in the third person but make it a little bit epic.

In your story, you can make yourself a brilliant inventor or a genius problem-solver. What would your character do?

Or you can invent a new character who has exactly the know-how you need. Ask the wise old wizard or your inner IT guru what they would do next to solve the problem.

This helps you break out of taking yourself so seriously, but it also helps unlock that part of you that already knows what to do.

6. Switch strategies

If you’ve been working hard on the building part of your project and it’s just not going well right now, switch to the drawing or planning part.

If you’re working hard on writing out your plan and you’re stumped, switch to gathering materials or drawing illustrations, or just start building and see if it helps you with your writer’s block.

It’s okay to jump around in the procedure as long as you keep moving forward.

7. Get silly!

When I was young, my dad, also an educator, used to call taking a small problem too seriously “awfulizing”.

When I was young, my dad, also an educator, used to call taking a small problem too seriously “awfulizing”.

It’s easy to awfulize a problem when you’re deep in your frustration. Awfulizing increases your frustration by making it seem worse.

Put a clown nose on the crisis and inject a little humor into the situation. You’ll be surprised how it can free up your creative problem-solving function. When you’re doing this with your child, make sure it’s clear that you’re not making fun of them for having difficulty—be silly, not sarcastic.

Amelia had the opportunity to practice these skills during our engineering project sessions. I explained a handful to the whole class and asked them to pick their favorites to practice. I also model them at every opportunity.

Within a few weeks, Amelia was starting to help other students when they were stuck, calmly and independently working to solve their problems with them, trying several different strategies to make things work. She didn’t give up when things got hard, and her behavior problems in class vanished completely.

If your child is having a hard time dealing with frustration, you can help them learn how to manage it better. Children will learn coping strategies for frustration one way or another—as Fine Parents, we can help them learn successful coping skills instead of self-destructive ones.

Practice by Making

A great way to help your own children practice these techniques to overcome frustration is to try a project together.

Tinkering or making things together offers lots of opportunities to get frustrated and solve problems. Not every project is ideal for developing frustration management, though—you need to hit a sweet spot of difficulty for your child’s age and ability level.

The project should offer the opportunity for you and your child to work more or less equally, although you might be doing different parts of the project.

Avoid especially tedious projects that seem designed to frustrate you, like the 50,000-piece working miniature railroad made of toothpicks. You’re looking for hard fun, not hard knocks.

Here are a few examples:

1. Making Play Dough

Materials: Flour, water, salt, food dye.

Sweet spot: 3 to 7 years old.

Mix flour, water, and salt in different proportions and adjust to make a dough of your preferred consistency. One easy recipe can be found here, but for the purposes of learning to deal with frustration, you might look at several recipes and improvise.

Frustration points to prepare for: Too much flour, too much water, making fine adjustments to the consistency; for young children, getting the ingredients into the bowl and cleaning up the mess!

Best techniques: Make frustration a friend, take breaks, notice and describe what’s happening.

2. Picnic Tower

Materials: Plastic forks and spoons, a tape measure.

Materials: Plastic forks and spoons, a tape measure.

Sweet spot: 6 to 11 years old.

Assemble a collection of plasticware forks and spoons, and work with your child to try to build a tower taller than they are. No tape or glue allowed!

Frustration points to prepare for: Broken fork tines, towers collapsing right before they can be measured.

Best techniques: Take breaks at intervals, replace “I can’t…” with “I can’t … yet”, and get silly!

3. Light-up Cards

Materials: Construction paper, copper tape and/or aluminum foil, 3-volt coin cell battery, various colors of through-hole LEDs, clear tape.

Sweet spot: 8 to 15 years old, or older—everyone likes to make stuff light up!

Frustration points to prepare for: Copper tape getting stuck to itself, poor conduction through the adhesive side of the copper tape, difficulty designing a circuit that works.

Best techniques: Notice and describe what’s happening, take breaks, change your perspective by telling a story, or switch your strategy when what you’re doing isn’t working.

You can find more projects to try in these helpful books:

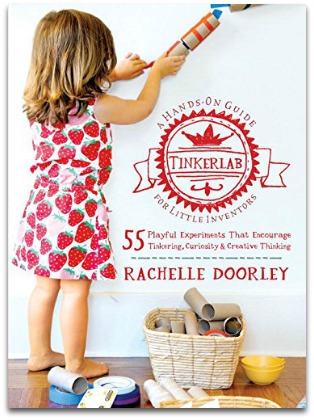

Tinkerlab: A Hands-On Guide for Little Inventors

Tinkerlab: A Hands-On Guide for Little Inventorsby Rachelle Doorley. Best for parents of young children, this book includes excellent hands-on science and art projects for 3–6-year-olds.

- The Art of Tinkering

by the Karen Wilkinson of the Exploratorium’s Tinkering Studios. More a book of inspiration than a how-to guide, this book is nonetheless designed to be hackable, with a conductive cover you can make light up!

- Tinkering: Kids Learn by Making Stuff (Make)

by Curt Gabrielson. This book curates some of the nearly infinite projects of Make Magazine, selecting those most accessible for kids, including making some magnet-based toys, catapults, and musical instruments.

The 2-Minute Action Plan for Fine Parents

For our quick contemplation questions today –

- Reflect on how you deal with frustration in your child’s presence. What are three things you usually do, and what are you (intentionally or unintentionally) modeling for your kids?

- Have you ever discussed about the different ways of dealing with frustration with your child? Have you explained that frustration might feel uncomfortable, but it’s not actually bad?

- When was the last time you and your child had to deal with frustration together? How did you each respond? Did you make the best of the teachable moment? What would you do differently the next time you find yourself in a similar situation?

The Ongoing Action Plan for Fine Parents

- Make making and tinkering a regular part of your time together. Seek out opportunities to work on projects together in order to practice frustration management while having fun!

- Invite your child to be an ally to you in your frustrating moments by reminding you of the techniques, so they can practice. (It’s not helpful, however, to make them responsible for your frustration; you need to be in charge of you.)

- Select a few projects to offer your child that might push their skill level just a bit. Let them pick their favorite of the ones you’ve chosen, and work on it together.

- Over a course of time, show them evidence of growth in their ability to deal with frustration effectively.

This is a great article. However, we have tried many of these things but sometimes these strategies work, often they don’t, and sometimes they backfire. Our child recently went through a neuropsychiatric eval (at age 7) and was diagnosed with anxiety, OCD, ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, and is borderline genius IQ. What do you do with kids like that? We are hesitant to medicate but things are getting a little too difficult to not consider this option.

Very nice article. I particularly like adding “yet” to “I can’t” because it acknowledges that “I can’t” is a fair statement, just not an endpoint.

My son has been struggling a lot lately because he’s 9, but advanced in most areas for his age, and he’s only now starting bump up against things in his education that don’t come easy right away. I keep trying to explain that other kids found out what it was like to be frustrated with math or reading much earlier than this, so emotionally he’s in a much younger place when it comes to these issues. Thanks for the extra ideas to play with.

Thank you for reading, and your comments. When my own is frustrated, which is often (he’s two, and has ambitions that far outstrip his ability!), it helps me to remember that his emotions are valid, even though his expression of them may be inconvenient. I try to remember that it’s possible for anyone to have trouble expressing perfectly valid feelings in productive ways, and because he’s so young, the set of options he’s learned for expressing himself is really limited. So rather than thinking that he shouldn’t be so frustrated because he can’t drive the car right now, I turn my thoughts to what I can help him do that will be a better way of coping with or expressing his frustration. We’ve been building with blocks a lot lately, and I’ve been modeling delighted surprise and curiosity whenever our elaborate towers fall over.

This is a wonderful article! I have a little one that struggles greatly with frustration – I might as well ?. It has been hard for me to guide him because his emotions are valid. I love the book suggestions and the idea that tinkering can help with frustration, as well as many many other educational skills!